Previously the complexities of saddle fit, and the importance of correct saddle fit in relation to equine health and performance have been discussed (see previous blogs). To add to the complexities, we must not neglect the effect that the rider has on the horse (and saddle) but also the effect that the saddle has on the rider. In respect of the saddle, there are multiple factors which can have an influence on rider biomechanics, seat size/shape, waist/twist, panel content, stirrup bar positioning just to name a few.

Knee blocks come in all shapes and sizes and their function, to provide support to the rider and aid positioning. Over the last decade, knee blocks have increased in size and design, largely driven by the rider, in an attempt to provide greater support and security. Although this mechanism could be interpreted as a benefit, the effect that knee block design/size can have on rider biomechanics and consequently the effect this has on the horse’s locomotion should not be underestimated.

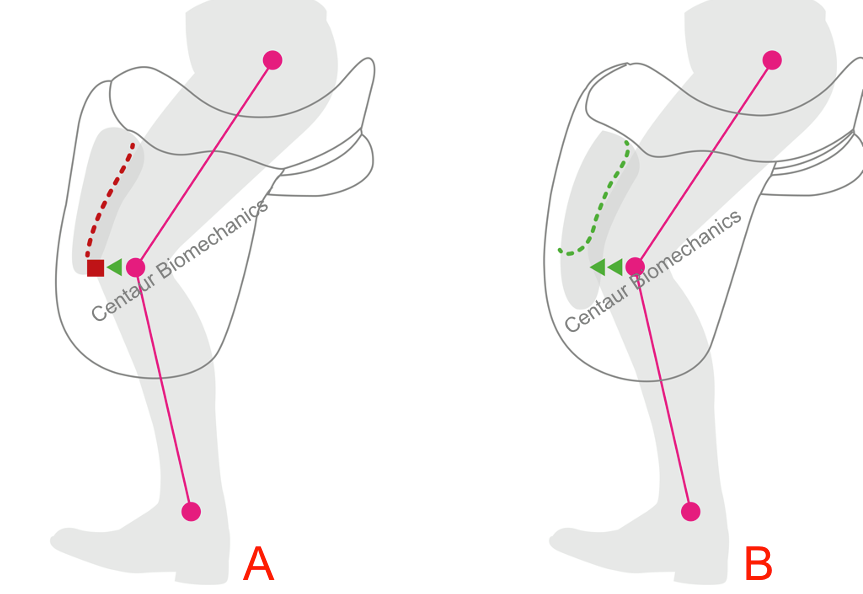

During locomotion, whilst maintaining dynamic stability, the rider has to manage and absorb propulsive forces being generated by the horse. In gaits where there is a suspension phase (trot and canter) the riders’ segments (pelvis, trunk, limbs etc) respond differently during each component of the stride. In the context of the knee block, following the suspension phase, during stance, the rider’s knee/thigh moves forward and can be pressed up (restricted) against the knee block. Depending on the size and shape of the knee block and anatomy of the rider, if restrictive, the rider’s pelvis can restricted. In a rider model, the segments are stacked on top of the pelvis, if the pelvis is restricted as a result of the knee being restricted by the knee block, then the segments above will have to compensate.

Recently we have demonstrated the effect that knee block design can have on the rider’s biomechanics and equine locomotion. With knee block modifications, allowing the knee to move forward (i.e. not being restricted by the edge of the knee block) the riders pelvic function was improved with a more neutral position being achieved throughout the motion cycle. The riders were more synchronised with the movement of the horse. This makes logical sense, if the pelvis is neutral (not restrcited) then force absorption and transmission can be better achieved. It would seem logical, like other parts of the saddle, that knee block design would influence rider biomechanics, however, we should not underestimate the effect that knee block design can have one equine locomotion, as a function of altered (restricted) rider biomechanics. With knee block modifications, allowing the rider’s knee to be less restricted, allowing the pelvis to be in a more neutral position resulted in alterations in the horse’s back movement and limb kinematics in trot and canter.

As previously said, horses will develop a locomotor compensatory strategy to alleviate any discomfort caused. In the case of a knee block, where the rider’s knee is restricted by the knee block, resulting in the pelvis being restricted, may have an effect on the horses back and limb movement.

Following on from the previous blog(s), I hope this helps and further highlights the complexities with saddle fit for both horse and rider and the importance of working with a qualified saddle fitter who understands these complexities from both a horse and rider view point.

Please like / follow our page for more blogs and please share to raise awareness ??

Dr. Russell MacKechnie-Guire

Centaur Biomechanics

www.centaurbiomechanics.co.uk

#equineresearch #biomechanics #centaurbiomechanics #veterinarymedicine #equinephysiotherapy #equinetherapist #onlinecourses #onlineseminar